Once the decision was taken to cancel the 5 Rivers Expedition (an expedition planned to run five rivers in Victoria, NSW and South Australia), the way was clear to run an expedition in Western Australia.

After heavy rainfall in early February in the upper Murchison, I decided that it was feasible to organise an expedition through the Murchison Gorges.

This would be the follow up expedition to the highly successful March 1994 trip from Milly Milly Station to the Galena Bridge, a journey of 400 kilometres along the Murchison River.

This 1995 Expedition was to be a 125 kilometre journey from Galena Bridge on the North West Coastal Highway through the gorges of the Kalbarri National Park to the mouth of the river at Kalbarri. The unknown but suspected dangerous nature of the gorges indicated the need for inflatable dinghies. Members of the cancelled 5 Rivers Expedition had first crack at being involved, then previous members of the Murchison River Expedition.

The trip was planned for the period 2 – 6 March (a long weekend).

Mike Lenz very quickly organised a flotilla of five inflatables. A shortage of experienced drivers with race ready motors was a temporary problem but one that was soon overcome.

Tropical Cyclone Bobby’s path of destruction and heavy rainfall crossed the headwaters of the Murchison on 24 February, ensuring that there would be water in the river by early March.

Initial indications from my telephone calls to pastoral stations along the length of the Murchison were that conditions would be ‘right’ for the planned dates, however, phone calls over following days elicited more information, prompting me to postpone the Expedition to 9-13 March.

All was in readiness by the long weekend before the trip. With a complement of fifteen the Murchison Gorges Expedition would be the biggest venture since the 18 man Darling Descent ‘82.

Reports from various sources indicated that the water level would be ideal. Cyclone Bobby’s rainfall had created the biggest flood on the Murchison River in nearly fifty years and it was to peak, virtually to the hour, as the Expedition departed from Galena Bridge.

The weather conditions and forecast were good and it looked like being perfect for the first power dinghy trip through the Murchison River Gorges.

The Murchison River

At 832 kilometres in length, the Murchison is Western Australia‘s second longest river (after the Gascoyne at 865 kilometres) although, depending on how the course of the Gascoyne is determined and considering the Hope/Yalgar extension, a case could be made for the Murchison to be hydrologically the longer watercourse . More Information.

The Start

The fifteen members of the Murchison Gorges Expedition left Perth on Thursday evening and drove through the night to arrive at the Galena Bridge on the North West Coastal Highway just before daybreak.

- At Eneabba.

- Hooking up the Landcruiser to The Bus.

- Whiling away the time with a deck of cards.

- Asleep in The Bus.

Navigating the lower 125 kilometres of the Murchison River over the next four days would complete the first journey along the length of the river.

- Water across Coolcalalaya Rd called for a change of plans.

On arrival at the Galena Bridge we crossed it and drove down to the old bridge. It was 400 mm under water. We later determined this to be the peak of the flood.

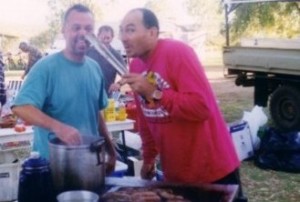

I allowed two hours to prepare the boats, clean out and repack The Bus, prepare breakfast, make lunches and plan the first leg.

- Preparations.

- Phil Hargrave making breakfast.

- Stretch checked out the depth of the river.

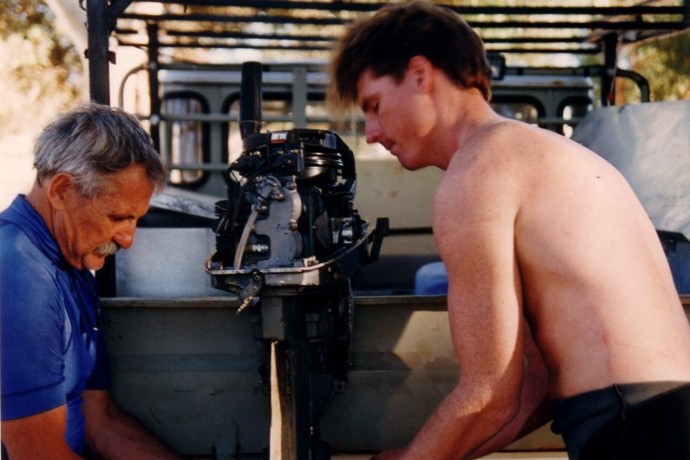

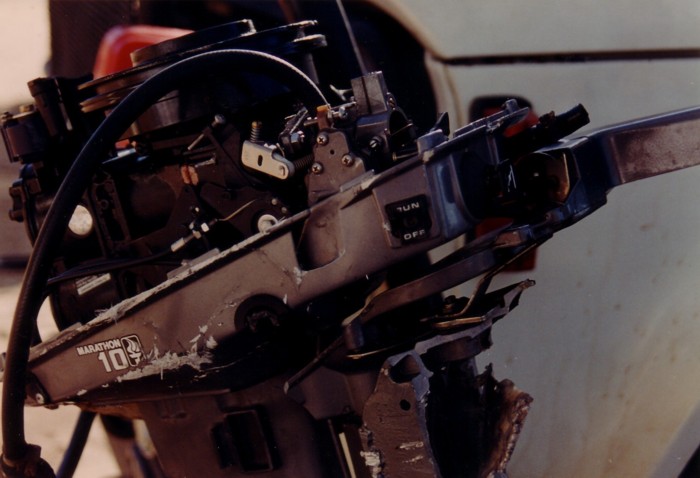

Phil Hargrave’s ducky was not a purpose-built race boat and, while it had performed admirably in the 1994 Murchison River Expedition, it was deemed wise to put some drain holes in it. Shane Kelly and ‘Techscrew’ Tony Overstone cut two holes in the transom that, while not ideal, were better than having none at all and would help it cope with the expected rapids and standing waves.

- Tony Overstone

While all this was being done I was sorting out the crew combinations.

“Tay was having second thoughts about going in the boat so I hightailed it to the top of the roof rack and Snooksie drew the short straw.” – Kim Thorson.

David Whitney and Tony Overstone set off in the 4WD ten minutes before the boat crews. They were to follow tracks close to the river, heading to the disused Geraldine Mine area. They planned to follow these river tracks as far as possible, keeping as close a check as possible on the boats.

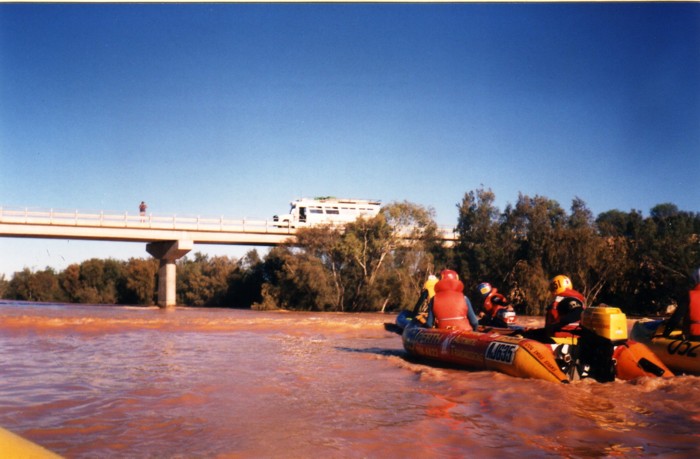

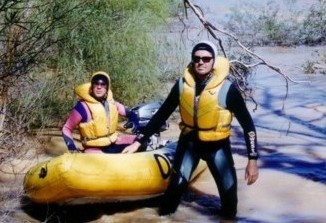

The boat crews left the Galena Bridge just after 8.00 a.m. Mike Lenz and Dave Snooks were in the Nav Boat. Cliff Hills was driving his rubber duck, teamed with John Haynes; Bill Breheny was driving his blue skinned inflatable with Cameron Wilkie as his co-driver; Adrian Bock was teamed with Scott Overstone; and Shane Kelly was driving Phil Hargrave’s V-hull inflatable.

- Leaving Galena Bridge.

- Leaving Galena Bridge.

The boat crews checked the first set of rapids carefully. Three ducks portaged the obstacle – just being careful – and Adrian and Scott, and Cliff and John shot it.

The fuel filter on Shane’s motor caused problems just after the Start. Remedial action did not take long and he and Phil were back into the fray.

- Sorting out carby issues.

- Cruising

- Stretch and Bill

- Into the trees.

- Above Hardabut Rapids.

After seeing the boats off from the Galena Bridge I headed off in The Bus to Ross Graham Lookout with Kim Thorson and Tay Overstone .

- Ross Graham Lookout

- Ross Graham Lookout

The Power of the Murchison

Tony and David had seen the boats at the planned checkpoint just a few kilometres down river from the Start. They then sped off to meet up with The Bus crew.

David decided that a section of river, shown on the map as being accessible by a track, looked potentially nasty. He decided they should check on the boats at this point.

As David and Tony crested a hill in the Landcruiser they saw a huge rapid that stretched as far as they could see in both directions, up and down river.

“I hope they don’t go into that.” — David Whitney after first seeing the rapid.

“Too late, they’re already in it.” — Tony Overstone, in reply.

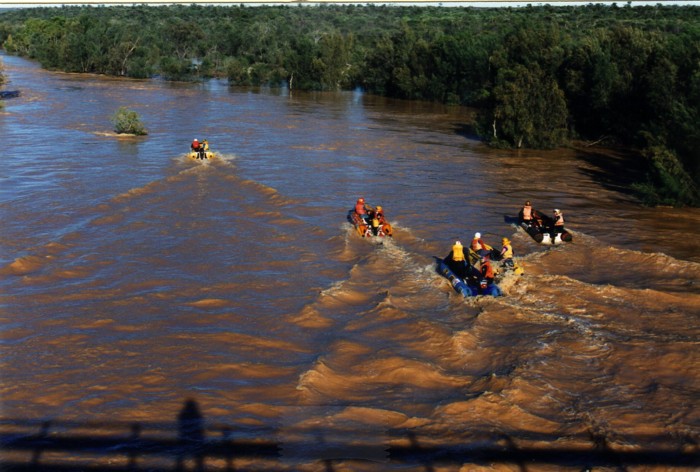

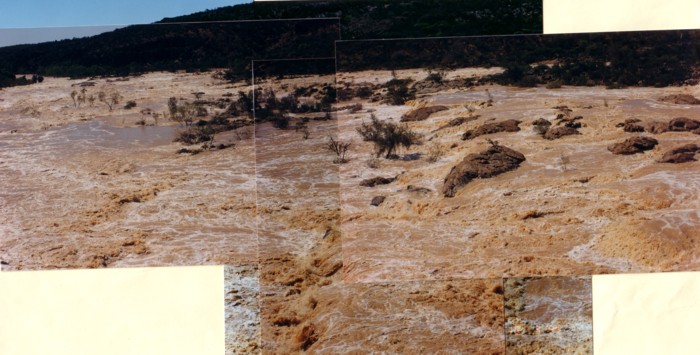

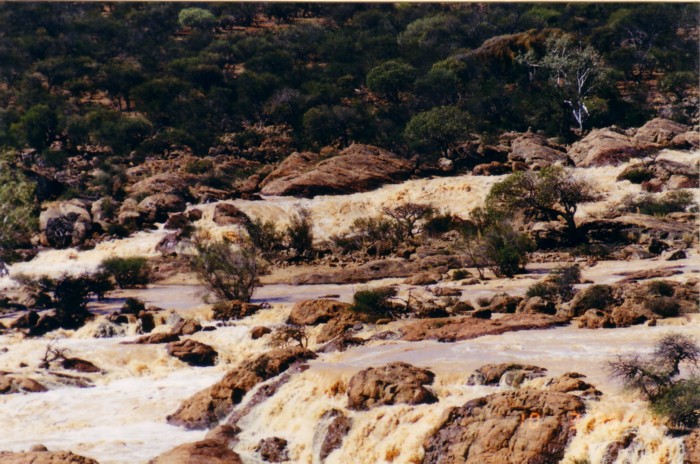

The Hardabut Rapids, fourteen kilometres down river from the Galena Bridge at the edge of the Kalbarri National Park, are about four times as wide and six times as long as anything on the Avon River.

- The Entry to Hardabut Rapid.

Their length, scope and power can only be properly seen from a vantage point accessed by the rough bush track Tony and David found. An aerial survey the day before by Mike, Cliff and Adrian did not reveal the true nature of Hardabut Rapids.

- Top of Hardabut

- The top of Hardabut.

- The top of Hardabut.

The relatively flat water approach gave those in the dinghies no idea that they had hit such a substantial obstacle, although the country had changed from flat flood plains to steep rocky hills. The Hardabut Rapids drop about forty metres over their 1200 metre length in a confusion of raging, white-flecked, brown water. The massive volume of water charging through innumerable drops, falls and shoots was difficult to comprehend. The speed of the water was frightening. Estimates varied from twenty-five to thirty kilometres per hour.

- From the northern bank.

The roar of the water could be heard over the outboard motor. On land it could be heard before one got out of the vehicle. The earthy smell from so much mud and silt in the water was immediately obvious. Spray pumped out from dozens of points.

- Hardabut in flood.

There was no safe route through this awesome spectacle. In fact, there was no defined route at all. Even if one could select a course through the extended length of the mighty Hardabut Rapids it is doubtful that one could line up or even remember each twist, turn, drop and shoot.

- 1.2 kilometres long.

Known by some as The Washing Machine, at peak water level the Hardabut Rapids are frightening. The puny power of an 8hp outboard motor, or even a 20hp, was no match for the river.

- Big drops

- Double storey rapid.

Coupled with the wildly aerated water it was a case of the river taking the boat where it wanted rather than a driver negotiating a route through.

- A big rapid.

The power of one huge seventy metre shoot on the far side of the river was awesome. This speeding freight train of water with a huge stopper rock and a four metre hole at the bottom could only be seen clearly through the binoculars – and had to be seen to be believed. It was through here that all five dinghies were drawn.

- The main shoot on the far bank.

The Hardabut Rapids are difficult to compare to any rapid on the rivers in the south of the State. The obstructing rocks were the size of houses. The drops were bigger than the boats and the volume of water going over them was enormous. The powerful backswirl trapped boats and bobbed them about like corks, spitting them out randomly.

- Hardabut Rapid

Dinghy racers sometimes use the expression “It’s really pumping” when some of these southern rivers are at a high level. These rivers are like a water pistol in comparison to the Murchison in flood.

The passage of the five boats through Hardabut was a moving disaster. Boats were tossed around like matchsticks in a maelstrom. The power of the water forced the nightmare downstream. Crews were thrown from the inflatables into the boiling, brown water.

- Awesome

Mike and Dave, navigating, were first into the Rapids. To them it looked the same as previous rapids they had passed through. They decided to continue. They powered through three or four standing waves, each one getting progressively bigger.

Mike couldn’t hear the noise of the motor over the constant roar of the water. The aerated water caused the motor to cavitate. It lost drive.

Drive or not, the river took them to the left of a huge rock. Water going over the rock but it dropped off to the left. There were more rocks to the left. Mike and Dave were funnelled through this gap. The water was being deflected off the rocks to the left causing a great turbulence. They dropped five metres into a stopper, on an angle, over a twenty metre stretch.

The back of the boat dropped vertically straight into a hole. The bow wasn’t at the top of the stopper. The height of this stopper was greater than the boat’s 3.5 metre length.

The boat was rotated clockwise and both Mike and Dave were thrown out. The boat went over the top of the stopper and sat on the other side of it. Mike and Dave were drawn through it.

Mike surfaced and grabbed his boat. It took off downriver. As he went over the next drop he lost hold of the boat and was taken further out into the river. He went over another three or four drops, each up to two metres in height.

Mike had travelled about seventy five metres from where he had been tossed out of his boat when he was swept over a shoot and into a two metre stopper.

“The stopper held me for a while until I was able to kick off from the rocky bottom. I surfaced and got a quick breath of air before I was pushed down again. This happened three more times. I pushed up, grabbed a bit of air and was sucked back down. I can’t remember how many more times it pushed me around. I started to run out of air. I thought I was going to die. Thinking it was all over I relaxed. It spat me out the bottom. I wasn’t sure where I was. I saw a rock and clawed my way up it”.

- Mike Lenz

Dave was pushed closer to the bank. He too was trapped in a stopper.

“I thought it was all over.” – Dave ‘Rowdy’ Snooks.

- Dave Snooks

PFDs (lifejackets) were totally ineffective in the roaring waters.

Cliff Hills and John Haynes were second into Hardabut.

“As we came around the corner it didn’t matter where you looked – there was white water everywhere.” — John Haynes.

Cliff and John covered the first 400 metres of the Rapids, crashing through violent standing waves before pushing down into the main shoot.

They survived to the bottom of the shoot when they were shot up onto a rock, slid off it and fell three metres to the bottom. They then shot straight up into a standing wave that flipped the duck 180o backwards. The shoot held the duck for about five minutes.

After being swept over a set of falls they were washed downstream several hundred metres.

“The standing waves were three metres high.” — John Haynes.

- John Haynes

Adrian Bock and Scott Overstone thought they had hit ‘the rapid from Hell’.

“We were having a hoot through some radical standing waves.” — Scott Overstone.

They dropped off a three metre wall of water and went straight up and over a two metre rock (they thought it was a standing wave – the noise told them otherwise). After successfully negotiating the most dangerous shoot in the whole Rapids they were able to pull over to the bank and assess what was happening around them.

“As far as we were concerned there was no drama until we saw that there weren’t enough heads.” — Scott Overstone.

Mike was lying on a rock thirty metres off the bank, not moving. John was still stranded but seemed okay.

Cliff and Dave were not to be seen. To the great relief of Scott and Adrian, they eventually appeared walking along the bank from upriver.

At the top of the Rapids, Cameron Wilkie yelled to Bill Breheny to, “Turn!, Turn!” There was no reply. Bill had been thrown out. Cameron drove the boat to the bank, threw a rope to Bill and pulled him in. They rested and assessed the situation with Shane Kelly and Phil Hargrave who had joined them. Shane did not like it and said so. However, there was no option but to head downriver.

They set off for their adventure. The ‘fun’ started at the first drop when the cowling came off. They hit a second drop.

“The motor took a gutsful of water and it was all over.” — Shane Kelly.

Shane was thrown out and when he surfaced all he could see was another huge drop. Phil dragged him back into the boat. The boat turned sideways into a tree and then went over another drop. At this stage survival was the uppermost thought in their minds.

- Shane Kelly

They managed to get the dinghy into a quiet corner and were then able to assess the disaster.

Later, they attempted to rope the dinghy down a shoot to the point where the other crews were assembling. The force of the water ripped it out of their hands. It caught in a smaller stopper near the scene of the main disaster. After a time it popped out, got caught a few more times and eventually snagged on a rock in a shoot, from where Cameron later recovered it.

- Phil’s boat trapped in a back swirl.

It was then turn for Bill and Cameron to try their luck. According to Bill the Rapids had “the eyes of a tiger and the soul of the Devil. It looked real wild”.

“What are you going to do?” asked Stretch.

“Hop in and hang on!” yelled Bill.

- Bill Breheny

They went upriver for a run at the ‘Devil’. All hell broke loose. The motor cavitated. The boat was washed sideways through a stopper to the bottom and filled with water. Bill was thrown out.

“Bill was clinging with all his strength to the rear pontoon. I leapt down the back, grabbed his left arm and pulled with all my strength but was unable to hold him. The raw power of the water pulled him down out of my sight like suds going down a plug hole.” — Cameron Wilkie.

Cameron was unable to see him for at least thirty seconds. He popped up twenty metres downstream, coughing and gasping for air.

“I hit the rock head first. My helmet was torn off by the force of the water. I couldn’t do anything about it.” — Bill Breheny.

Cameron was sucked into the drain Bill had just disappeared down. He was pinned against a rock, unable to budge for twenty seconds, and thought he was drowning. He bobbed up and gulped in a breath of — foam.

Bill and Cameron swam ashore and joined Adrian, Cliff, Dave and Scott at the assembly point. The boat was headed towards Kalbarri, upside down.

John was stranded in the middle of the shoot like a shag on a rock. He could see Mike lying down on a flat rock ten metres away but could see no-one else. On looking down river all John could see was another 200 metres of steep rapids with lots of drops. Exhausted from his ordeal, John had no intention of moving from his position of relative safety.

Some lunch bags floated by. A little while later Bill’s blue inflatable floated past. John grabbed at a rope at the front of the boat but was unable to hang on to it.

When Bill first saw Mike after his ordeal he thought that he “did not look 100%, more like 20%”. Scott attempted to throw a rope to Mike who was closer to the bank than John. He was unable to get the rope out far enough.

Ten minutes later Stretch came along by himself in Adrian’s boat and picked up John from his perch, delivering him to the northern bank.

- Cameron rescued John.

Stretch dropped off John, returned to the rocks and rescued Mike.

Meanwhile, Shane and Phil and joined up with the main group.

- The boat crews assembled at an island below Hardabut.

Although Adrian and Scott made it safely through this shoot (by going over the rock) and indeed the whole mighty Rapids, it is impossible to guarantee a successful attempt. The other four dinghies were sucked in, chewed up and spat out.

- Hardabut Rapid

Cliff’s boat had popped off the stopper that was holding it and took off downstream. Cliff, Bill and John eventually found it snagged on a tree. The motor had a broken swivel bracket and no cowl.

Cameron and Adrian took off in Adrian’s boat (the only working rig) in a search for Bill’s boat. They found it snagged on a lone tree just fifty metres above another rapid (about Grade 3), 600 metres downriver from the bottom of Hardabut.

They towed it to where David Whitney (land crew) was waiting on the southern bank.

Adrian stayed there with David, and Cameron drove across the river to the assembly point. He collected Cliff’s rig and towed to the southern bank before once again returning to the main group at the assembly point.

- Adrian at the bottom of Hardabut.

On the other side of the river it was more than thirty minutes before Tony and David, the two land crew, could visually confirm the safety of the ten boat crew.

Tony then sped off in the 4WD on a forty kilometre round trip to find The Bus Crew of Kim Thorson, Tay Overstone and me at Ross Graham Lookout.

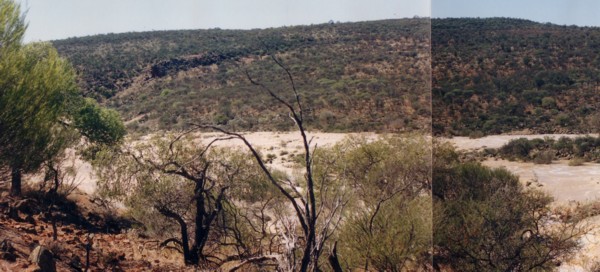

When The Bus crew had arrived at the Lookout earlier they walked 300 metres to a vantage point overlooking the speeding water.

“It looks dangerous to me.” — Tay Overstone.

They had been waiting for so long they reasoned that the boat crews must have struck trouble.

“They had 30 kilometres to do and the current was flowing about 30 kilometres per hour. After waiting for two hours it didn’t take too much to know they were in trouble.” — Kim Epton.

Tony’s arrival just confirmed what they suspected.

“The boat crews are in trouble. This rapid is 100,000 times worse than anything you’ve ever seen before – and I’m not exaggerating.” — Tony Overstone.

The Support Crew of David Whitney and Tony Overstone arrived at Hardabut just as the boat crews were starting to sort themselves out and assemble on an island near the bottom of the Rapids.

One of the first sights for the Support Crew after they arrived at Hardabut was to see Stretch attempting to reach Mike’s boat. He had donned two PFDs and, using a fuel tank for extra buoyancy, attempted to make his way across the raging river to where the craft was stuck. The current was too strong and swept his legs out from under him when he was only two metres from Mike’s boat. Finally he had to let go of the tank and float down river. He stopped on a rock about 100 metres from another shoot where Phil’s boat was trapped.

“It was extremely dangerous rafting this rapid without a raft. My situation was not good. I was out of reach of ropes. The (working) boat was 800 metres downstream. Only option was to swim and hope. I noticed Phil’s boat. I jumped into the water and steered myself towards it on my back.” — Cameron Wilkie.

- Cameron attempting to get to John’s boat.

- Cameron attempting to get to John’s boat.

He caught hold of the throw rope. After twenty minutes he had freed the boat.

Immediately below his location was a large, dangerous whirlpool. Cameron pushed the inflatable into the current and, holding the tow rope, leapt over the shoot, hoping the boat would drag him through.

His daring, courage, skill and awareness saw him safely to the bank.

After righting the inflatable he piloted it down to the assembly point in an exciting ride, standing up and holding onto the tow rope.

- Planing without a motor.

It was decided to no longer pursue the recovery of Mike’s boat. All boats and gear were moved to the assembly point.

- The boat crews assembled at the one location.

- Mike and John after being rescued.

- Assessing the situation. Bill’s boat (in background) already retrieved to southern bank.

The Support Crew on the southern bank was unable to assist in any part of the recovery operation until craft and crew crossed the current.

Tony, Tay and the two Kims were scrambling over the rocks to get to the water’s edge when David Whitney appeared from the spot where Bill’s boat and Cliff’s rig had been dumped.

“It might need stitches.” — David Whitney holding his hand up to show a cut finger.

He had slipped while carrying Cliff’s motor and had been cut by the cav plate. Tay took David into Kalbarri for medical attention to what was far more than a simple cut.

Meanwhile, Cameron Wilkie piloted the only working boat and ferried each person and the other boats, one at a time, across the raging current.

The on-water crew and the land contingent were eventually reunited at this point on the southern bank, about two kilometres down from the vehicle access point.

After an assessment of the situation it was obvious that the first stage of the Expedition was over and the boats would have to be retrieved from where they were. It was a daunting task.

Mike Lenz’s boat was irretrievably trapped in the middle of the Rapids – after an hour of effort it was deemed to be too dangerous to make further attempts to free it.

- A difficult situation.

The next four hours were spent hauling four boats, motors and gear up steep, rocky slopes in 40oC heat. The sharp spiky low shrubs, spindly scratching shadeless trees and scattered spinifex slowed the seemingly endless task.

- All the gear had to carried about two kilometres.

- Cooling off from 40 plus degree heat in between carrying equipment back to The Bus.

Finally it was time to call a halt. Everyone was exhausted. Equipment was strewn over a two kilometre trail from where the boats had been recovered to where The Bus had been able to reach. The loss was substantial. In monetary terms it added up to over $12,500 including inflatable boats, outboard motors, spare propellers, handheld radio, compass, heliograph and other sundry items.

“I lost a runner.” — Adrian Bock.

Kim Thorson had the forethought to erect a shelter at the rear of The Bus that provided shade for the exhausted crew as they returned.

“Staminade and glucose tablets were going down as fast as the crews were.” — Kim Thorson.

Thirteen weary expeditioners climbed onto The Bus and into the 4WD for the fifty kilometre trip into Kalbarri.

- Cameron ‘Stretch’ Wilkie did a magnificent job in the recovery phase.

The extent of the floodwaters was immediately obvious as I brought The Bus to the top of Meanarra Hill, over-looking the town. A brown stain from the river pushed out into the crystal blue sea for two or three kilometres. It extended up and down the coast for many kilometres.

After booking into a caravan park the rest of the afternoon was spent showering, sleeping and recounting the story of how lucky each person was to escape alive and in a place that required only a two kilometre struggle up the steep rocky slopes of the river valley.

That there was no loss of life was fortuitous. Both Mike and Dave were breathing water when trapped under the giant shoot. Mike later had treatment at Kalbarri for water on his lungs and an injured knee. John Haynes badly injured a knee that swelled dramatically and kept him on one leg for the remainder of the trip. He subsequently had a week off work. The injuries were not confined to the boat crews.

Not long after the recovery operation commenced, David Whitney was carrying an outboard motor up the near vertical slope when he trod on a loose rock, slipped and dropped the motor. The cav plate nearly severed the little finger of his right hand. After attention at the Kalbarri Nursing Post he was driven into Geraldton Hospital where he had microsurgery under general anaesthetic and stayed overnight.

“During the whole weekend Dave never mentioned his misfortune. I admire his style.” — Bill Breheny.

- David Whitney

The late afternoon and evening was spent recounting the journey down the Rapids ‘at least twenty times’.

- Chatting with the Ranger.

- Bill and Mike with a damaged motor.

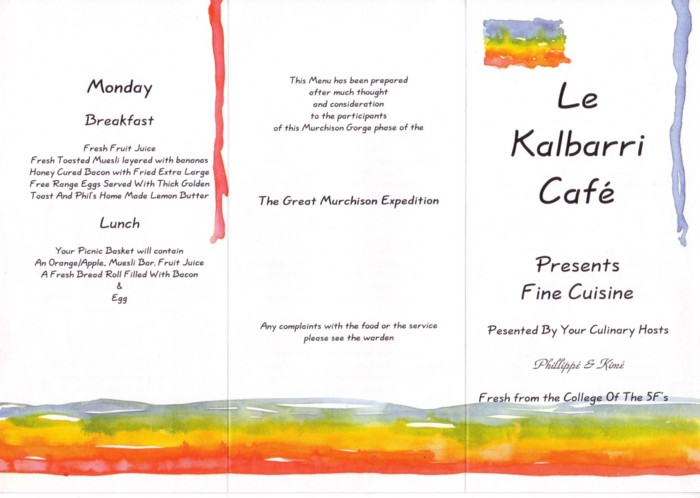

We advised the local Ranger of what had happened and told him we would sort out the situation ourselves. Kim Thorson and Phil prepared a magnificent meal and afterwards, with others, regaled the crowd with hilarious stories.

When things are going wrong, when people have just been through adversity, when it’s hot, when the terrain is challenging, when the work is tough and energy sapping and when everyone is tired, it’s a recipe for disaster. But we had a good crew and, most importantly, good food prepared by good cooks.

Phil and Kim provided not just good food but excellent food – as good as one could wish, quality restaurant standard and plenty of it. So important!

- Phil Hargrave

- Kim Thorson

Postscript to the evening meal – the fridge had frozen the lettuce. Tony and I located some at the local fish and chip shop – the final cost of lettuce (combining ruined and replacement) was $5 each. An expensive salad.

“The Murchison makes the Avon look like the last day of the Blackwood.” — Shane Kelly.

“I’ll never worry about going down Emus again.” — Cliff Hills.

“The standing waves were so big I couldn’t see the boats in front.” — Cliff Hills.

“Nothing on the Avon will ever worry me again.” — Bill Breheny.

Murchison Bushwalking

No-one was relishing the task confronting them. Even though a lot of hard work had been put in the day before, a big job awaited the Team to finish the recovery of the boats and equipment.

- Waking up.

- Let out for the day.

- At Kalbarri

- John had a swollen knee.

John Haynes remained at the caravan park to rest his badly swollen leg. Mike Lenz also had to rest his injured knee and elected to drive the hire car into Geraldton and pick up David Whitney.

The remainder headed out of town in The Bus and the 4WD. Fifty kilometres later at Hardabut Rapids the heat of the sun was felt before the job started.

The Recovery Team was split into two groups. One group helped Tony pick a path through the bush for the 4WD. He was able to crash the vehicle through the scrub to a point about midway between the clearing where The Bus was parked and where the boats had been left.

- The ‘cruiser picked up a stake when going cross country.

Although the exercise cost a staked tyre, any reduction in the distance the boats had to be carried was a relief.

The other group removed an eight metre annexe pole from The Bus roofrack and carried it into where the boats had been left.

Each boat in turn was deflated and lashed to the pole. With three men at the end of each pole the task of recovering the boats and other gear from the mountain goat territory was considerably easier.

- Deflating a duck prior to carting it back to The Bus.

- The annexe pole from The Bus was put to good use.

- Taking a break.

- Through the scrub.

Scott summed up the recovery operation when he succinctly stated:

“Lift Drag Drop Drink.

Lift Drag Drop Drink.

Lift Drag Drop Drink.

Lift Drag Drop Drink.”

- Scott and Bocky

- Two more to go.

- It was hot and hard work.

No-one knew precisely where David had left the motor the previous day after it cut his finger. Kim Thorson and Cameron Wilkie located the finger-crushing motor after a short search. It was 50 metres up a cliff. They made a harness from a throw rope and carried it back to The Bus.

By 1.30 p.m. all boats were loaded on the roof rack of the 4WD. It had taken four hours. Bill Breheny and I guided Tony along the tyre tracks through the scrub to where The Bus was parked – nobody wanted another staked tyre.

- Tony drove the Landcruiser through the bush back to The Bus.

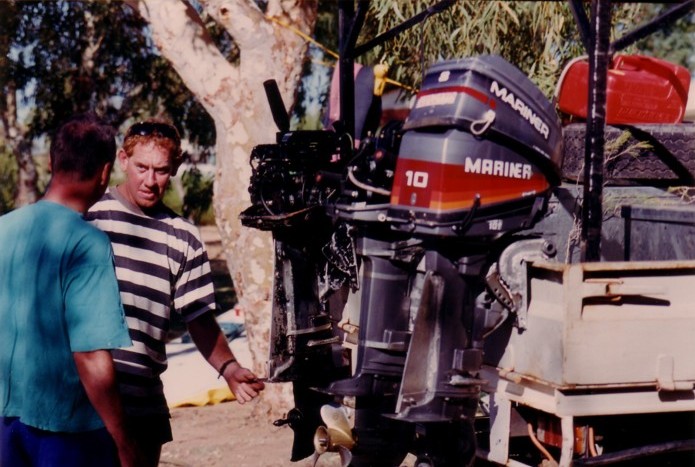

On return to the caravan park at Kalbarri damage was assessed and the boats were prepared for a run up the river the next day.

- Phil and Shane

- At Kalbarri Caravan Park.

- Cliff and Cameron fitting a new gearbox.

- At Kalbarri.

- Busted motor.

- Sunset at Kalbarri.

Bill Breheny’s motor was wrecked (although it still ran). Damage to the boats was minimal – mostly scratches caused when being manhandled, carried, pushed, dragged, and pulled up the steep sides of the river valley.

Spare motors were brought out and eventually four boats were readied.

The remainder of the afternoon was spent resting – well deserved after two days of toil in hot and hard conditions.

Phil and Kim prepared another superb meal.

- Kim’s Kitchen

After dinner Kim regaled the crew with the ‘Tale of the Headless Seagull’.

The Murchison Gorges

After a leisurely start on Sunday, Adrian, Cameron, Bill, Cliff, Kim Thorson, Phil, Scott, and Tay prepared to go up river from Kalbarri to The Loop – a distance of about fifty-five kilometres. One boat was unable to get off the start line and so Bill Breheny and Scott Overstone jumped into the back of the 4WD as part of the Support Crew.

- Starting from Kalbarri.

- Phil and Cliff waiting to start the upriver adventure.

- Phil and Cameron

- Cliff on the way upriver.

- Adrian and Kim

- Showoff

The muddy tidal waters at Kalbarri were slowly left behind as the crews in the remaining three boats fought against the fast flowing current.

Mike and Shane and I went to Murchison House pastoral station in The Bus to rendezvous with the boat crews. After an exchange of pleasantries the boat crews continued their battle upriver against the swift current and The Bus crew headed for The Loop. At the entrance to the National Park (The Loop and Z Bend road) a newly installed ticket machine presented them with the problem of finding $5 worth of the correct coins.

“Pay five bucks and give your vehicle a rattle test on the corrugations.” – Shane Kelly, who had recently been along the same tracks.

The vibrations from the badly corrugated track to The Loop caused the freezer door to fall off and the screws holding the cooling grille at the rear to come out.

- The door of the freezer has fallen off.

After ‘playing tourist’ without seeing the boats (and not expecting to see them) The Bus crew returned to the caravan park, unaware that the boat crews arrived at The Loop only minutes after they left.

With Tony driving, David navigating, and Scott and Bill in the back of the Landcruiser, the refuelling team followed the boats nearly to Murchison House on a different track to that taken by The Bus crew.

Scott relates what happened:

“The Brain’s boat stopped so we jumped in the back of the Landcruiser to what we thought would be a quick trip to The Bus, only to find ourselves at the mercy of Fangio on acid and the Silent Assassin’s weird sense of fun. That meant two guys levitating in the back of a ute at 70 km/h with a loose spare wheel, two jerry cans, two fuel drums, and a hi-lift jack for company.

After half an hour of brain shattering bumps we came to the river and could hear the boats. Because we were slightly hidden by trees I started to wade out. Realising I couldn’t go any deeper I thought I would swing through the trees for a better vantage point only to find teenage mutant ninja ants the size of my thumb not overly impressed with my presence in their tree. They were very hungry after two weeks stuck up a tree that is normally attached to the ground and not in two metres of water.

- Scott in tree.

- Scott in water.

The boat crews had seen my dinghy decky death dance avoiding the ants and pulled over. Everything OK.

- Don’t worry, Bocky!

- Action Man

- Cooling off.

We continued on with Fangio and the Assassin only to get bogged to the axle in mud. Out of the mud and back to the bumps.

- Bogged

A noise started that meant something was broken. We stopped. One rear spring broken and one spring bent. We limped back to camp.”

- Scott Overstone

After the effort of the first two days, the boat trip up river was certainly a change of pace. Fantastic scenery. If the boat crews didn’t already know the river was in flood their trip through the tops of the trees would certainly have given some indication that there was more water than normal. The ‘flats’ of Kalbarri gave way to the gorges and ranges.

The colourfully stratified cliffs were magnificent and in some places were almost perpendicular. Lunch was eaten in the shade of a gum tree at the base of one of these 60 metre cliffs.

- Looking downriver from The Loop.

Approaching The Loop, the boat crews noticed people on the north side of the river. Kim Thorson takes up the story.

“We saw it was the Rivergods rafting gurus. I asked them if they knew where we were. They answered ‘in the Murchison River’. When asked where exactly we were on the river, the ‘God’ pointed downstream stating, “Kalbarri is that way”. We then realised that they were not intelligent life forms and offered them beads, mirrors, and tobacco to ensure our safety.

Stretch was talking to a female from the tribe who was busy applying mud in a ceremonial style to her body and face. We were still trying to establish our location. He mentioned that we had seen some people further down river but they couldn’t have been our Support Crew because there was a skirt.

The female tribe member seemed to take offence and demanded to know what he meant by ‘skirt’.

Seeing Stretch drowning in a pool of feminism I jumped into the cauldron boiling before me, “A skirt meaning that it was either a tourist or one of our boys has taken to cross dressing, which if the latter, I know who I’ll be sleeping with tonight.” Stretch was saved and the tribal feminist was pacified.

Meanwhile another one of the females of the species had lined up Cliff for a strange face painting ceremony. She had already got strange symbols painted on his face.

Fearing the worst, we distracted them by pointing upwards saying, “Look, a dead duck!” We escaped with our virginity and sanity intact! I’m sure they’re still there.”

Half way through The Loop the crews decided to turn back because of a shortage of fuel. The boat crews had underestimated the amount of fuel usage against the powerful current on the upriver journey.

The trip downriver gave an impression of going downhill. The trees were very thick and as the river flowed out of the gorges it spread to a width of about a kilometre.

- Heading downriver to Kalbarri.

After some quick calculations, it was realised that not all the boats would reach Kalbarri on the amount of fuel remaining. Adrian and Kim gave their paddles to the other crews, grabbed all the fuel tanks and set off downriver to get more fuel. There was no fuel to be had at Murchison House and they continued on towards Kalbarri.

“Bocky asked if we had enough fuel to get to Kalbarri. I said yes but I was lying.” – Kim Thorson.

About three kilometres from Kalbarri the flow of the river met with the incoming tide to produce turbulence that ‘shook fillings loose’.

- Adrian Bock

About a kilometre from the caravan park Adrian’s motor began to miss and splutter. Kim elevated the tank to get the last precious vapours into the ailing motor. As it turned out Kim wasn’t lying – they had enough fuel to reach the park under full power. Adrian refuelled all the tanks and headed off alone up river to meet with the other two boats and their crew.

It was late in the day before the boats returned. Problems aside, the consensus was that it was a great trip through magnificent gorge country.

- Arrival at Kalbarri.

- Preparing to launch the rubber ducky.

- Packing up.

- Get him, Scott.

- Loading boats onto The Bus roof rack.

- At Kalbarri Caravan Park.

Once again Kim and Phil prepared a magnificent meal. Before the flambé could be served for dessert the ice cream had to be retrieved from the mobile home next door where the owners had kindly stored it in their freezer. Someone forgot to tell Bocky that it was guarded by Australia’s biggest alsation/rottweiler cross. He returned with a face as white as the ice cream.

“Phillipe and Kime served food that wouldn’t be bettered at the Parmelia.” – Bill Breheny.

Revisit, Retrieval and Return

Everything was loaded for the Monday trip home.

- Breakfast at Kalbarri.

- Preparing to leave Kalbarri.

We made a quick tour of Kalbarri before heading home.

- At Kalbarri.

- Mouth of the Murchison in flood.

- Overlooking Kalbarri.

On the way the Team called into Hardabut Rapids to see if Mike’s boat could be retrieved. The water level had dropped considerably. The flow of water through the rapid had decreased markedly. Even though the power of the water was reduced the Rapids were still awesome in extent.

- On the track into Hardabut.

Mike and Cameron were out of The Bus before it was even parked. After a short time looking for his boat, Mike could not see it and walked away, obviously disappointed.

- The group spent some time looking for Mike’s boat.

- Three days after the peak it is still a huge rapid.

Cameron persevered and spotted the boat quite a distance down river from its previous position. It was free, upright and being held in position by the throw rope jammed between rocks. Cameron, Scott and Kim Thorson volunteered to retrieve the rig.

- The boat had shifted.

Adrian’s boat and Tay’s 10hp motor were lowered down a near-vertical cliff to a quieter section of the river.

The flow of the water was still more powerful than what would be encountered in southern rivers.

- Looking downriver from the retrieval point.

- Looking upriver from retrieval point.

Cameron’s request for a spare fuel tank was ignored and, had it not been, may have made the recovery quicker and easier (but perhaps more risky). The three jumped into the boat and took off at an angle downstream. Kim was dropped at a rock island part way to where Mike’s boat was stranded.

- Lowering Adrian’s boat down the rock face.

- Launching the retrieval boat.

- Prepping the retrieval boat.

- The retrieval starts.

- Going out to get Mike’s boat.

The motor ventilated (cavitated) badly in the turbulent water.

Despite repeated attempts, Scott and Cameron were unable to reach Mike’s boat by going up against the flow of the river. Scott was left on an exposed rock below the blocking rapid and Cameron tried four more times before he successfully made it to the boat. He dragged the boat onto some rocks and assessed the situation.

- Kim was left on a rock.

- Cameron reached the boat.

Cameron tells his story:

“The only way to get the boat back was to drive it. There appeared to be 50% water in the fuel tank. If somebody had listened to me we would have had a spare tank (spit, spit – Ed.). I took out the tank from Adrian’s boat to use on Mike’s motor. After several minutes of cleaning and TLC I was able to start the motor.

I had to improvise a tank. A round, one-litre, plastic lunch container was the answer. I used a prop to drill a half inch hole in the lid. Chopped off fuel line and bunged tank with tilt pin. Filled up makeshift tank with fuel and washed out. Started motor to check all was OK. Excellent. Would have passed scrutineering!”

Cameron loaded Mike’s boat sideways across Adrian’s boat and drove down to where Scott was waiting. Both were ‘melting’ in their wetsuits.

Attempts to drive Mike’s boat up a shoot were unsuccessful. The jack was jammed and would not allow the motor to be lowered far enough into the water to get sufficient drive. Eventually Cameron ferried Scott, Kim and the boat back to the waiting Support Crew, one at a time.

- Cameron laid Mike’s boat on Adrian’s boat.

- Cameron returns Kim to shore.

It took a frustrating hour to retrieve the boat and just as long to get the smile from Mike’s face.

- Coming ashore.

- Mike’s boat retrieved.

- Mike’s boat.

- Mike inspects his motor.

Hauling the two boats and motors up the cliff and back onto the roofrack of The Bus was hard work but a least on this occasion the distance they had to be carried was only about 100 metres.

- Hard work.

- Dragging the boats up the rock face.

- Kim with a motor.

Both vehicles returned to the bitumen and the 4WD was hitched to The Bus. I was behind the wheel for the first section of the long haul to Perth. On checking the rear vision for the first 100 metres I noticed that the 4WD seemed to be tracking strangely. A check revealed that the wheels of the 4WD had turned full lock when the vehicle moved from the gravel to the bitumen and had then dragged/scuffed/rolled along the black top, leaving a trail of rubber and removing the lugs from the front tyres.

- The Bus roof rack was repacked.

- Hitching 4WD to The Bus.

In the past, when ‘A Framing’ a vehicle behind The Bus, the steering wheel had been securely lashed through the windows of the vehicle so it could not move at all. This caused scuffing when corners were turned. On this trip it was not tied at all. The optimum arrangement is for the steering wheel to be moderately restrained by an ocky strap or similar.

During the trip home there was already talk of a future trip to the Kalbarri Gorges, perhaps a hike on foot to investigate the rapids between Hardabut and The Loop.

- Cliff, Scott, Mike and Cameron.

- Inside The Bus.

- Sneak attack.

- Cliff, Phil, Kim and David.

- Checking the load at Geraldton.

- The obligatory ‘group photo’.

The mobile phone repeater at Geraldton was placed under great pressure as The Bus passed through the service zone.

Headwinds at Greenough (as per usual) slowed The Bus to what seemed like walking pace.

Near Eneabba a rumbling noise was heard coming from the rear axle area on The Bus.

“It’s the diff.” – prophet of doom, Adrian Bock.

“I think it’s the diff.” – another prophet of doom, Cameron Wilkie.

“I hope it’s not the diff.” – Kim Epton, payer of the bills.

Checks at the Eneabba Roadhouse failed to find anything wrong. After continuing a few kilometres the smell of burning rubber was obvious. The Bus was quickly stopped. To the amazement of many the inside rim, made from 8mm thick steel, had shattered – a victim of the rough bush tracks The Bus had travelled and wheel studs that had worn unevenly.

- Spectators

- Shattered rim.

Investigation at Kenwick Motors after the Expedition showed that all five studs were badly worn. They were replaced with a different type of stud that more positively located the inner rim. The studs on the right rim were also changed as a preventative measure.

The Murchison Gorges Expedition was over. Six guys had seen their life pass before their eyes. That is not what are expeditions are all about. We got a scare and were lucky to emerge unscathed.

There is still 14 kilometres of the Murchison to do.

© Kim Epton 1995-2024

7670 words, 151 images.

Feel free to use any part of this document but please do the right thing and give attribution to adventures.net.au. It will enhance the SEO of your website/blog and Adventures.

See Terms of Use.