From the west, the Eyre Highway starts at Norseman and stretches 1671 kilometres to Port Augusta.

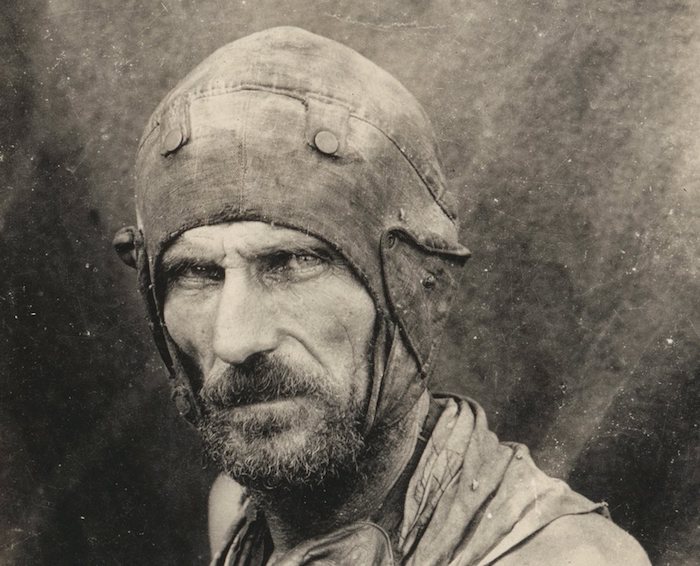

The Eyre Highway is named after Edward John Eyre (1815-1901), who, in 1841, with his aboriginal companion Wylie, made the first land crossing of Australia from east to west.

Eyre, together with his companions John Baxter (1799-1841) and three aboriginal youths (Wylie, Joey and Yarry), departed from Fowlers Bay (south of Nundroo) in South Australia to traverse the continent following the coast. There was insufficient feed for the horses and the journey developed into a nightmare of heat, flies, hunger and thirst.

- Edward John Eyre

- Wylie

South of where Caiguna is now situated Joey and Yarry shot and killed Baxter and ran off with many of the provisions. Eyre, with Wylie, an aboriginal from the King Georges Sound tribe, pushed on westward and eventually met with a French whaling ship, the Mississippi, that was anchored in Thistle Cove, near what is now Esperance.

The English captain of the ship, Rossiter, looked after the explorers for several weeks during the extreme winter weather, until they regained their strength. They then continued their epic journey, reaching Albany, a further 560 kilometres westward, five months after setting out. The continent had been crossed and Eyre was the toast of the colonies.

In 1870 John Forrest (1847-1918) and Alexander Forrest (1849-1901) set out from Perth to find a practicable route around the Great Australian Bight to Adelaide. They travelled farther inland than Eyre, seeking water and assessing the land for pastoral purposes. The east-west telegraph line erected in 1875-77 followed the country mapped by the Forrest brothers for much of its route. This line enabled Perth to be linked to Britain (by a very circuitous route that went through Albany, Israelite Bay, Eyre, Eucla, Adelaide and Darwin).

- John Forrest

- Alexander_Forrest

Camel and bullock teams left a track during the construction of this east-west telegraph line. Prospectors who headed to the Coolgardie Goldfields from the eastern colonies in the 1890s followed this track from Eucla to Esperance. From Esperance, they headed along a northwards route (known as Dempsters Track because it wound through the bush to Fraser Range Station which had been settled by the Charles and Andrew Dempster in the 1860s). From Fraser Range the diggers continued northwest to Coolgardie. When Norseman was declared a municipality in 1896 the overlanders began to follow a more direct route via Noganyer Soak, on the western shore of Lake Dundas. Later, a new path that left the original overland track north of Point Dover was made in a westerly direction to Balladonia and Fraser Range. This eliminated the Esperance corner, greatly shortened the way to the goldfields and ultimately decided the route of the modern road.

Eyre blazed the way for the highway, Forrest made the preliminary survey, pastoralists and linesmen established a rough track, overlanders (such as the hopeful diggers making their way to the WA goldfields) gradually confirmed it, and world events forced its proper establishment.

In 1912, Francis Birtles crossed in a 10 hp Brush Car.

- Francis Birtles

By 1924 only three more vehicles had made the journey. A Citroen driven by Noel Westwood and G.L. Davies left Perth in August 1925 and returned in December 1925 after having circumnavigated Australia. Hubert Oppermann, later to become a MHR and the Australian High Commissioner to Malta, cycled from Cottesloe to Bondi Beach in 13 days in 1937.

Until the outbreak of World War II in 1939 no surveyed road existed west of Penong, in South Australia. Fear of invasion by the Japanese enemy from the north of Australia forced hurried construction of a road to military specifications in 1941. Construction was a joint civil and military project. Work began simultaneously from the east and west. The centre line was pegged and the road was formed by grading in the natural soil from the sides. No attempt was made to raise the formation above the natural surface or to drain the hollows. The two passes from the top of the Hampton Tableland to the Roe Plain – at Madura and at Eucla – were the only sealed sections along the entire route.

Prior to this it was only a lightly formed track made during the construction of the telegraph line in the late 1800s, and kept in use by the pastoralists of the area.

In 1941 Cocklebiddy served as a camp for construction of the East-West Road. It was once the site of an aboriginal mission. The ruins are visible at the rear of the Roadhouse. The gazetted ‘road’ from Rawlinna to Cocklebiddy was used as a supply route from the Rawlinna railway siding during these hectic construction days of 1941-42.

Normally the completion of such an undertaking would have been front page news but with wartime security measures in place, no publicity was given to the project.

The Western Australian section was sealed in 1969 and in 1976 the South Australian section was sealed. Some sections that John Eyre, John Baxter and his party of three aboriginal youths traversed are now part of the highway that bears his name. However, to minimise traffic disruption, keep dust down and because the original road had minimal salvage value there was little benefit in closely following the existing formation when it was eventually sealed.

The East-West Road was named the Eyre Highway by the WA Nomenclature Advisory Committee in 1943, after agreement by the South Australia naming body.

In June of 1951 traffic averaged less than ten vehicles per day and by 1963 it was still only 40 vehicles per day. In this period grading and intermittent gravelling of sections maintained the road in reasonable condition.

However, even after the road was sealed it was still considered adventurous to cross the continent along the Eyre Highway.

- Another iconic sign.

The Hyden-Norseman track past Lake Johnston was originally part of the East-West Road. But for the economic strength of Kalgoorlie, the Eyre Highway may have been routed through Hyden.

- Signs such as this have become iconic as representative of outback Australian travel.

There are four sections of the highway used as an emergency landing strip for the Royal Flying Doctor Service – at Nullarbor, Eucla, Mundrabilla and Madura.

- A number of sections of the Eyre Highway are used as emergency air strips for the Flying Doctor.

Further Reading:

Bridge, Peter J. with Ian Murray, The Overlanders : Crossing the Nullarbor 1870s – 1970s, Hesperian Press, Carlisle, 2011.

Collins, Neville, The Nullarbor Plain – A History, Published by the Author, Woodside, South Australia, 2008.

Edmonds, Leigh, The Vital Link, University of Western Australia Press, Nedlands, 1997

Fuller, Basil, The Nullarbor Story, Rigby, Perth, 1970.

Gilleland, Ray, The Nullarbor Kid : Stories from my trucking life, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 2012

The reports of the various trips, tours and travels on the Adventures website have a lot of information about place names – their naming and features – toponymy. More information.

© Kim Epton 1988-2024

1153 words, eight photographs.

Feel free to use any part of this document but please do the right thing and give attribution to adventures.net.au. It will enhance the SEO of your website/blog and Adventures.

See Terms of Use.